Pointers, references, auto and an analogy

Topic

A look at how type deduction with auto (and templates) works the way it does when dealing with references and pointers.

Motivation

Pointers and references can be a source of confusion for newcomers to C++, as well as those well versed in the language. There is one school of thought that says, references and pointers are essentially the same. They compile down to the same assembly code and do the same thing under the hood. However at a language level, references and pointers behave very differently and this can lead to a lot of confusion (especially when interacting with other C++ features such as auto). The aim of this article is to help build a mental model for how to think about pointers and references, hopefully making how they interact with things like auto much clearer.

Example

Pointers and references provide the facility to refer to a value indirectly. This is incredibly useful but at times it might not always be obvious which to prefer. We learn early on that references can only be bound to a value once, whereas pointers can be made to point at something else even after they’ve been initialized (unless of course the pointer is marked const - see the digression at the end for more on this).

The key difference between a pointer and a reference is that a pointer has what is called value semantics. What this means is if you copy a pointer, you don’t copy the underlying value, you just copy the pointer (the thing with the address in it).

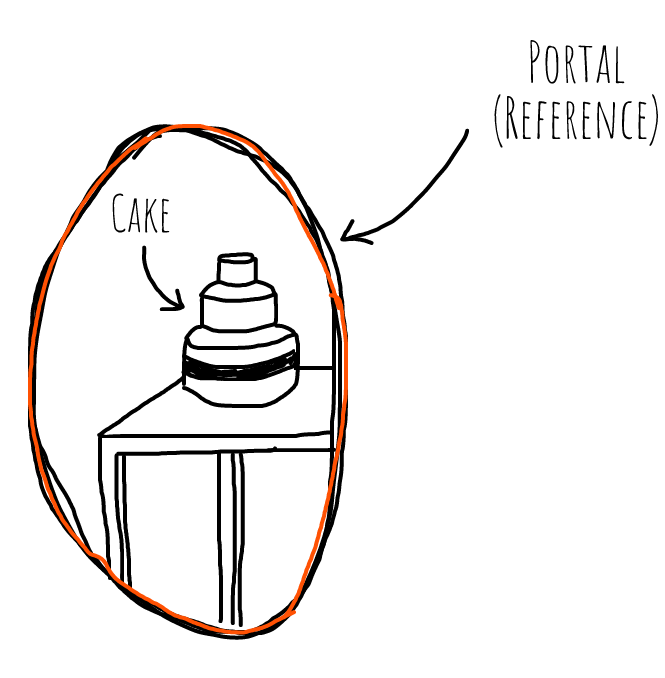

This is all very well but it’s a bit abstract. What might help is an analogy to better conceptualize pointers and references. The way I like to think about it is a reference is a ‘portal’, and a pointer is a small ‘teleporter’ device…

Picture yourself in your living room (in the distant future). Your favourite cake is sitting waiting for you at the bakery in the nearest town. You have two options when it comes to getting it. The first is to use a portal. You can open a portal in your living room that looks directly into the bakery and you can see straight through it to your cake.

The portal is this intangible outline that you can’t really touch, or do anything else with, but you can reach the cake and pick it up and take a bite, as if you were right there in the bakery. It’s possible to open more than one portal to the bakery, or even link (or chain) them if you so wish, but it’s impossible to actually copy one.

On the other hand, you could use a teleporter. The teleporter is a small box you can type some coordinates into, and when you press the big red button in the center of the device, you jump to the bakery and can access your delicious cake.

It’s pretty easy to have more than one teleporter, you just type the same coordinates in and it’ll take you there. In fact you can make as many as you’d like by 3d printing (replicating) teleporters, and so long as the coordinates entered are the same, you’ll end-up at the bakery.

With all that in mind, lets return to pointers and references. A reference is a lot like a portal. It creates a ‘window’ to another object as if it were right there. You can view (if it’s const) or mutate (if it’s not) the object directly through the reference just as you could reach through the portal and admire (or eat) the cake.

A pointer on the other hand, is a lot more like a teleporter. A pointer can’t give you the underlying object unless you dereference it (press the big red button). This takes you to the object to view or mutate it, and once you’re done, it will send you back to where you started. You can quickly copy a pointer, just as you can 3d print/replicate a teleporter, and it’ll take you to the same place.

Now where does auto come into all this? auto often behaves strangely to some people because it doesn’t deduce reference types. That is, if you have a function returning const Cake& such as

const Cake& GetCake() { ... }

And you write:

auto cake = GetCake();

The type of cake is not const Cake&, it’s just Cake. This is because the rules for auto follow the same rules as that of template parameter type deduction, which state ‘If template parameter type P is a reference type, the type referred to by P is used for type deduction’, which essentially means the reference type is totally ignored. With pointers though it’s another story. If instead our function returned const Cake* such as

const Cake* GetCake() { ... }

And we write:

auto cake = GetCake();

Then cake will have the type const auto*. On first learning this fact one quickly feels yet another reason to curse C++ and wonder who dreamed up all these insane rules, but on reflection it is for good reason and the portal/teleporter analogy from before helps us understand why.

When we use auto, it’s as if we put whatever value we have in the 3d printer. In the case of the teleporter this is fine, we just make another teleporter that can take us to the cake, but if we use the portal, we’ve actually just grabbed the cake itself and shoved it into the 3d printer, making an exact copy of the cake we then have in our living room. To ensure we do not make a copy of the object (or cake) we need to write:

const auto& cake = GetCake();

And we’ll bind to a reference instead of making a copy. Remember this is the exact same behaviour as if we were using normal types. If we write:

Cake cake = GetCake();

We get a copy, and if we write:

const Cake& cake = GetCake();

We’ll get a reference.

Deliberation

Hopefully this slightly harebrained analogy will resonate with some people (it might infuriate others, who knows 😅) but it helped me think about the way in which pointers and references behave, and why auto acts the way it does. Just remember pointers and references are different and it’s useful to appreciate how.

Digression

To read a C++ expression and know what the const applies to, it’s easiest to read the expression right to left.

1 int* a; // non-const pointer to non-const int (pointer and value can be changed)

2 ^ ^

3 const int* a; // non-const pointer to const int (west const) (value cannot be changed, pointer can be changed)

4 ^ ^ ^

5 int const* a; // note: This is equivalent to the above (east const)

6 ^ ^ ^

7 int const* const a; // const pointer to const int (pointer and value cannot be changed)

8 ^ ^ ^ ^

9 const int* const a; // note: This is equivalent to the above (west const)

^ ^ ^ ^

See above. On line 7, we say ‘a is a constant pointer to a constant int’, and on line 5, we say ‘a is a pointer to a constant int’. As it’s legal to put const on the left or right of a type, things don’t work quite as nicely on lines 2 and 9, but once you know the rule just lift the ‘west const’ convention in your mind to ‘east const’ and read the expression again (right to left).

Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more about C++, references and pointers, I cannot recommend the classic Effective C++, More Effective C++ and Modern Effective C++ books highly enough (written by the legendary Scott Meyers). Modern Effective C++ has an excellent chapter on auto which is well worth a read in particular.